An undivided real estate interest is a form of ownership in which several parties hold ownership of the same property. Unlike typical ownership, where one individual or entity owns the entire property (a “fee simple interest”), undivided interests mean that multiple owners each have use of the entire property. This is like fractional ownership of a business entity, in which several owners each hold a percentage of the same company. In real estate, undivided interests are common in inherited, family-owned, and investment properties.

For example, if three siblings inherit a house from their parents, each sibling might own one-third of the property. They all have equal rights to use the entire property, and none can claim a specific room or section as solely theirs. This shared ownership offers unique tax advantages, particularly when it comes to transferring ownership.

Tax Treatment: Typical Ownership vs. Undivided Interests

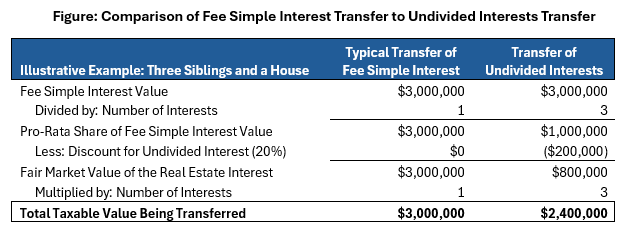

When a single property is transferred to a single recipient on a fee simple basis, the entire value of the property is considered taxable. This can result in significant tax liabilities, especially for high-value properties. For instance, if a property worth $3 million is transferred, the full $3 million value of the property is considered taxable.

Alternatively, transferring undivided interests in the same property can reduce the taxable amount. This is because partial interests are often valued at a discount compared to their pro-rata share of the fee simple interest. The discount reflects the challenges and limitations associated with owning a partial interest, such as the difficulty in selling the interest, the lack of control over the property, and potential disputes among co-owners.

The IRS recognizes these challenges and allows for valuation discounts on undivided real estate interests. These discounts depend on various factors, including the type of property, the number of co-owners, and market conditions. By applying these discounts, the taxable value of the transferred property is reduced, resulting in lower tax liabilities.

Example

Valuing a Residential Home

Let’s consider a practical example to illustrate the benefits of transferring undivided real estate interests. Suppose a residential home is worth $3 million, and the owner wants to transfer the property to their three children. Under typical ownership on a fee simple basis, the entire value of $3 million would be subject to gift or estate taxes.

However, if the owner transfers a 1/3 interest in the property to each child, then valuation discounts come into play. Assume a 20% discount is applicable due to the fractional nature of the transferred interests (we will cover how the exact percentage discount is determined in the next section). Here’s how the calculation would work:

- Transfer Partial Interests: The property is transferred to each sibling in three equal parts, each worth $1 million before discounts ($3 million / 3).

- Apply the Valuation Discount: With a 20% discount, each undivided interest is valued at $800,000 ($1 million - 20%).

- Calculate the Total Taxable Value: The total taxable value of the transferred interests is $2.4 million ($800,000 x 3).

By transferring undivided interests, the taxable value of the property is reduced from $3.0 million to $2.4 million, resulting in significant tax savings. This reduction can be particularly beneficial for estate planning, allowing more wealth to be passed on to heirs with less owed in taxes.

Tax Court Precedents for Undivided Real Estate Interest Discounts

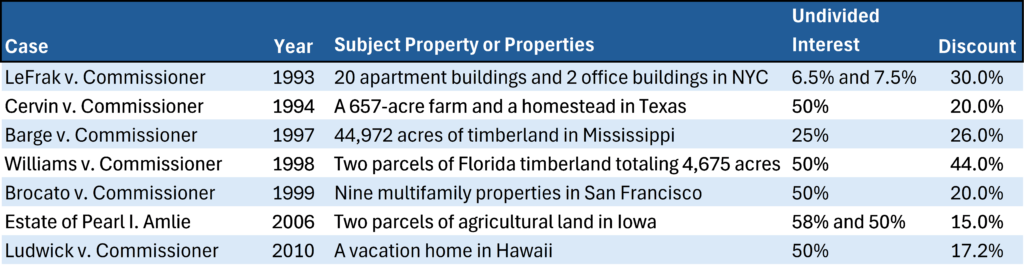

Discounts such as the one shown in the example above have been the subject of numerous Tax Court cases over the years. As always, the magnitude of the discount is based on the unique facts and circumstances of the subject interest in question. That said, a review of certain relevant cases and their ultimate resulting discounts shows that certain factors are associated with higher discounts. These cases are shown in the table below, followed by a discussion of the key factors driving higher discounts.

A Review of Relevant Cases

- LeFrak v. Commissioner: This case is notable in that the court accepted separate and distinct discounts for lack of control and lack of marketability, which is more typical of closely-held business valuations. In LeFrak, the court found that a 20% discount for lack of control and a 10% discount for lack of marketability were appropriate for various undivided real estate interests in income-producing New York City properties. The court accepted these discounts based on the factors typically utilized in business valuation, including the subject interests’ lack of ability to control the properties and the absence of an active secondary market for undivided real estate interests.

- Cervin v. Commissioner: In contrast to LeFrak, the court in Cervin concluded that a single discount of 20% was appropriate for two undivided interests in separate parcels of land in Texas. The taxpayer’s expert argued for a 25% discount based on lack of control and lack of marketability features like those cited in LeFrak. The IRS’s expert argued that discounts of 6.54% and 8.20% were appropriate for the two properties (a different discount for each), based solely on partition costs. The IRS’s approach in this case is one that we will see variants of again in subsequent cases; it holds that the fair market value of an undivided real estate interest is its pro-rata share of the fee simple interest, less the costs to compel a partition. However, in such cases where this approach is applied, the resulting discount is typically much higher than what the IRS argued for in Cervin.

- Barge v. Commissioner: In Barge, the court found that the fair market value of an undivided real estate interest is its pro-rata share of the fee simple value, less the costs which would be incurred to compel a partition. What made Barge unique is that the subject property was income-producing timberland for which the court developed its own discounted cash flow (“DCF”) analysis. The court’s DCF analysis in this case and in others like it (see the case of Ludwick v. Commissioner below) is useful because it gives us a framework for how to recreate the analysis for other properties. It is also notable that the court considered the time value of money in discounting the property’s future cash flows over a forecast period of 4 years. The concluded discount in Barge was 26%, although it must be considered that with a greater risk profile and a similar or longer time to liquidity, the court’s DCF analysis may have produced a significantly higher discount.

- Williams v. Commissioner: As in LeFrak, in Brocato the court accepted separate and distinct discounts for lack of control and lack of marketability which are more typical of closely-held business valuations. What makes Williams stand out is the unusually high discount of 44% which the court allowed, representing a cumulative 30% discount for lack of control and 20% discount for lack of marketability. This decision was at least partially due to the IRS’s poor performance at trial, leading the court to favor the taxpayer’s expert. It is also notable that in Williams, the court found that lack of control and lack of marketability features should be considered in addition to the cost of achieving a partition. The IRS’s expert proposed a 5% discount based solely on the cost to partition the property; the court found that such discount “does not give adequate weight to other reasons for discounting a fractional interest in real property, such as lack of control and the historic difficulty of selling an undivided fractional interest in real property…”.

- Brocato v. Commissioner: As in Williams, in Brocato the IRS argued that the applicable discounts for multiple undivided real estate interests should reflect only partition costs. This resulted in discounts that were relatively small as a percentage of the fee simple property values. However, the court concluded that it is also appropriate to consider “other factors, such as the historical difficulty in selling these interests and lack of control.” The court sided with the taxpayer’s expert, who successfully argued that a 20% discount was appropriate for the subject properties. What made Brocato unique is that the taxpayer’s expert based his analysis on eight actual comparable transactions of undivided real estate interests in the same market as the subject properties (the Bay Area of California). This is uncommon in Tax Court cases involving such interests, where neither party’s experts are typically able to identify any transactions involving truly comparable interests.

- Estate of Pearl I. Amlie: This case is similar to Brocato in that the taxpayer’s expert also relied on actual transactions of undivided real estate interests to determine the applicable discount. However, unlike in Brocato, the comparable transactions were neither recent nor in the same market as the subject properties. Some of the transactions had occurred several years or more prior to the date of the decedent’s death, and all were in eastern Iowa rather than northwestern Iowa, where the subject properties were located. The taxpayer’s expert argued based on these transactions that discounts ranging from 25% to 35% were applicable to the two subject properties. Such discounts would have been consistent with those allowed by the court in the past, but the court was not convinced that the comparable transactions were truly comparable to the subject properties. The court ultimately allowed a discount of only 15%.

- Ludwick v. Commissioner: Ludwick is the most recent significant Tax Court case that dealt with undivided real estate interest discounts. It is notable because, as in Barge, the court developed its own DCF analysis to quantify the loss in value resulting from a partition of the property and distribution of the ultimate sale proceeds. Because the subject property was a residence, it was deemed unsuitable for division into separate parcels. It is also useful for practitioners to see the court’s Barge-type analysis applied to a residence, rather than a commercial property such as the subject of Barge. The court’s conclusion of a 17.2% discount in this case is based on the present value of the future sale proceeds, net of the expenses incurred for property maintenance and selling costs. While this discount falls at the lower end of the range of discounts historically permitted by the court, it must also be noted that with different subject characteristics, the court’s DCF methodology may have produced a significantly higher discount. As always, the magnitude of any valuation discount is based on the unique facts and circumstances of the subject interest in question.

Key Takeaways From the Tax Court Cases

The Tax Court cases discussed above are not an exhaustive list of all cases involving undivided real estate interests, but they are significant ones which tell the story of how the court has interpreted discounts for these interests over time. By reviewing them, we can identify certain recurring themes:

- Undivided real estate interests are like non-controlling, non-marketable business interests. In business valuation, there is a well-established understanding that discounts for lack of control and lack of marketability apply to minority owners of private companies. The Tax Court has consistently applied these economic features to the holders of undivided real estate interests.

- There is a framework to quantify higher discounts. In Barge and Ludwick, the court was clear in its decisions that the applicable discount for an undivided real estate interest is based on the present value of a future liquidation resulting from a partition. Under the framework established by these cases, valuation practitioners can identify the features of a property which may drive higher discounts and perform an analysis around them.

- The specific facts and circumstances of the subject interest are key. The unique features of a property can vary widely. Ranch land in Texas is unlike a vacation home in Hawaii, but in both cases, the subject property has risk factors that affect the timing and magnitude of cash flows to the owner in a sale or partition. In performing a valuation analysis, the most defensible discounts will incorporate features specific to the subject property and the subject interest in the property.

Withum’s Real Estate Team Can Perform the Fee Simple Appraisal

An undivided real estate interest discount analysis begins with a fee simple appraisal. The applicable discount for the undivided real estate interest is then measured based on the pro-rata share of the fee simple appraisal. Our Real Estate Valuation Services Team at Withum can perform the fee simple appraisal, which may then serve as the basis for the undivided real estate interest discount analysis.

Transferring undivided real estate interests can offer a significant advantage for taxpayers looking to minimize their tax liabilities when transferring property. By understanding the nuances of fractional real estate ownership and applying appropriate valuation discounts, taxpayers can significantly reduce the ultimate taxable amount of the real estate being transferred. This approach not only provides financial benefits but also facilitates smoother estate planning and wealth transfer processes. If you’re considering transferring real estate, our experts at Withum can help you navigate these complexities and maximize your tax savings.

Author: Morgan Sansbury, CVA | [email protected]

Contact Us

For more information on this topic, please contact a member of Withum’s Real Estate Valuation Services Team.