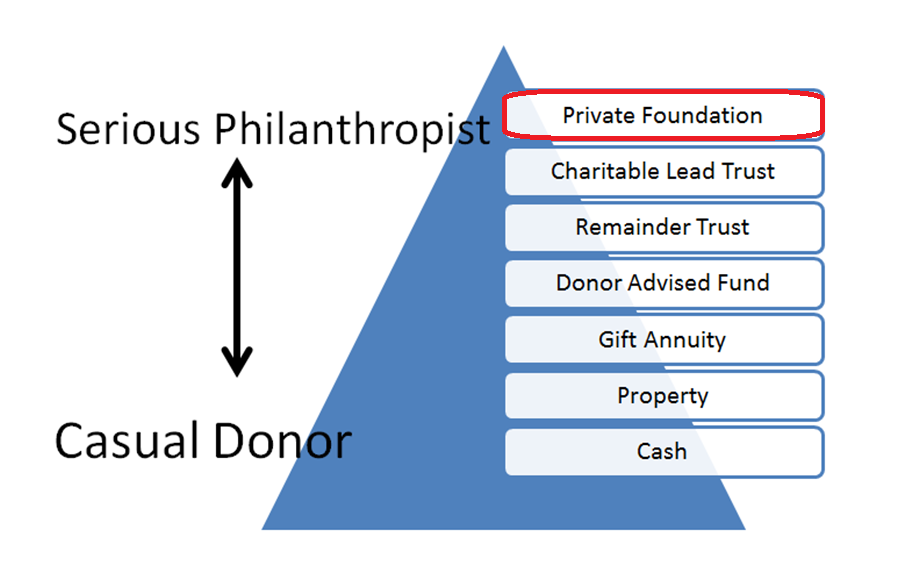

Tools & Techniques 101: The Private Foundation

We have reached it. The pinnacle of the Philanthropic Continuum. The stuff of upscale cocktail party chatter. The Cadillac, no, the Rolls Royce of philanthropic giving vehicles. Drum roll, please… introducing the PRIVATE FOUNDATION.

Now, for such a sexy vehicle you would think there would be a sexy name. Could it get any more boring? The term “private foundation” evokes yawns even from me as I write about it! But, like a good, solid (boring) CPA who is worth his/her weight in gold, the PF is a powerful construct and great addition to the philanthropic toolkit. Unfortunately, it is also an often overused vehicle, as we shall see.

My take is that private foundations work well for donors and families who want to be in the business of philanthropy. If, instead, you are merely looking for a charitable pocketbook, try a donor advised fund (DAF) – it works much better.

What is it?

A private foundation (PF) is essentially a private charity that is created, funded and (generally) controlled by a single donor or members of the donor’s family. PF’s can be either “operating” foundations (involved, say, in the running of a museum) or “non-operating” (grant making.) There are many more non-operating foundations that operating foundations in existence today and, for the most part, when we speak of PF’s we are speaking of non-operating entities. PF’s are far more robust that DAF’s because they can be used to more extensively fund charitable projects while exerting greater control over their outcome. The best use is for philanthropically inclined high net worth donors who want to maintain control of the charitable assets prior to disposition, establish the direction of charitable giving for their families and establish a family reputation as philanthropists for generations to come. As stated above, they are for donors who want to be in the business of philanthropy. In practice, however, I have too often seen those who are not that interested in charity talked into using a PF because it was a good income and transfer tax planning tool. But that is only half the equation with the other, perhaps more important half, being the donor’s charitable inclinations. It is always a shame when a PF, once funded, ends up languishing and being used as a mere charitable pocketbook. This is definitely not the best use of a PF.

Another bias on my part – if PF’s are best used for the business of philanthropy rather than as a charitable pocketbook, they ought to be a decent size. There is no legal minimum size for PF’s but in my mind, a practical minimum is seven figures or more. I know of, at least, one vendor who offers prepackaged PF’s for a minimum investment of $100,000… but really, how much “philanthropic business” can you conduct with such a small base?

PF’s are terrific, but like certain exotic, high performance sports cars, they are really high-maintenance vehicles. Like everything else, you have to weigh the pros and cons to see if such a vehicle is right for you.

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| From a planning perspective, the establishment of a PF works well for the philanthropically minded taxpayer faced with a major liquidity event, like the realization of a large bonus or equity compensation package, or the lucrative sale of the family business. This enables the taxpayer to shift the contribution to the year of the liquidity event, reduce taxes accordingly, and defer the ultimate gift to the final charity to a later date. |

Although lower cost options are available, the cost of administration is high including legal, tax, accounting, and management costs. |

| Once established and funded, the donor or, more appropriately, the board of the PF which may include the donor and family members, can exercise significant but not total control over the timing and manner of charitable expenditure. |

There is constant legal exposure to the PF, its board members and managers for excise taxes levied for not following the rules to the letter of the law. |

| There is also considerable flexibility in the choice of recipients. This is probably the most desirable feature for those who wish to be in the “business of philanthropy.” For example, PF’s are not limited to making only public charity contributions. Under certain circumstances, they can make grants to individuals or other private foundations. However, grants to individuals are permissible only by using an IRS-approved selection method and grants to other private foundations involve the donor-PF’s acceptance of expenditure responsibility. Such permissible uses of PF’s increase flexibility and often enable donors to use their PF’s to advance or support causes that are underserved or of little interest to public charities. |

The tax rules for PF’s restrict them to a greater extent that public charities. PF’s are subject to an ongoing, annual excise tax equal to 1% or 2% of net investment income. Public charities are not. |

| There are tax advantages to the donor such as avoiding the recognition of capital gains on highly appreciated assets donated to the foundation, and shifting income producing taxable assets from his/her own pocket to the tax exempt world of the PF. |

There are lower annual charitable contribution limitations for PF’s than for public charities (30% vs. 50% for cash; 20% vs. 30% for capital gain property). This may be meaningful for significant donors who periodically face these limitations when filing their income tax returns. |

| PF’s provide significant visibility in the philanthropic community, and can also be used to pull the family together in the pursuit of common philanthropic goals. |

The big one – the required annual minimum distribution of 5% of the PF’s asset value to other charities |